Repubblica presents, on occasion, articles written about heroes from the Civil War. As Americans we need to look back often at the people who built and influenced the country, many through fighting in wars that decimated people and property.

"To yield the field and fly was not to be thought of. We must stand or die."

— Colonel Archibald Gracie, 43rd Alabama Infantry

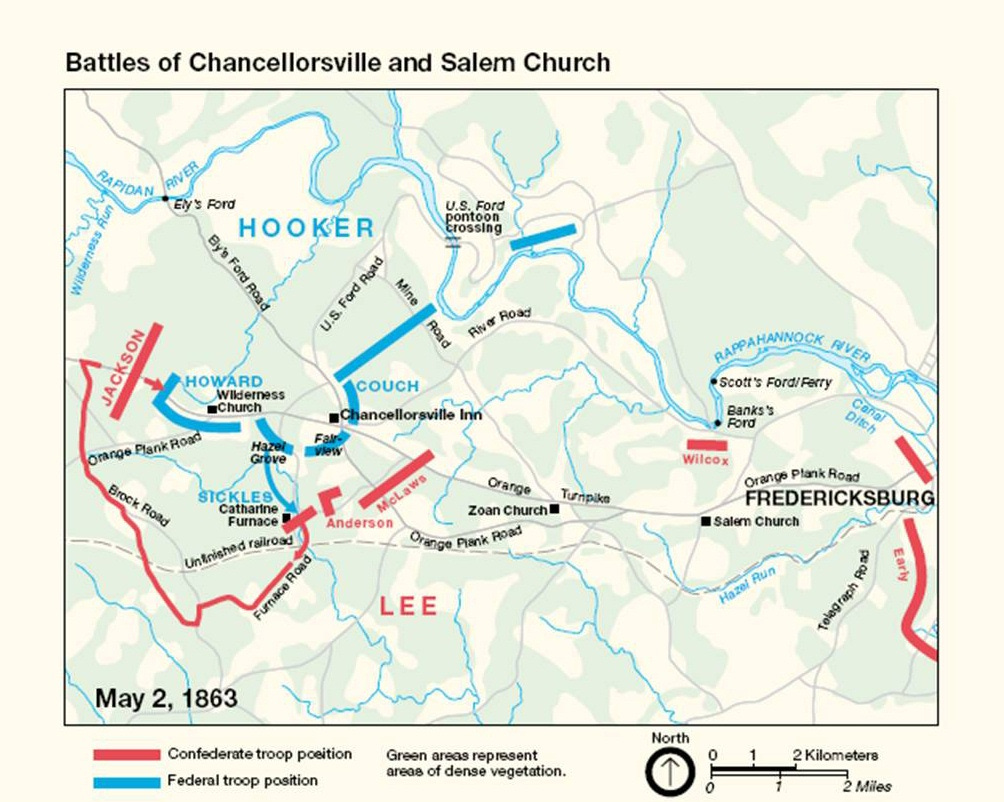

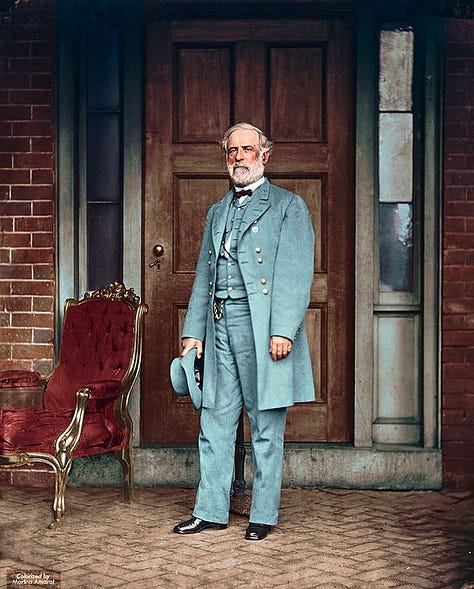

In the tangled thickets and shadowed clearings of Spotsylvania’s infamous Wilderness, Robert E. Lee engineered what many military historians have called the most dazzling Confederate triumph of the Civil War. The Battle of Chancellorsville, fought from April 30 to May 6, 1863, pitted the lean, aggressive Confederate Army of Northern Virginia—numbering some 60,000 men—against Major General Joseph Hooker’s well-fed and numerically superior Army of the Potomac, which boasted nearly 115,000 troops. Yet what unfolded over the course of seven chaotic days was not merely a contest of arms, but a study in terrain, willpower, command cohesion, and the limits of human endurance under fire.

Terrain: The Tyrant of the Wilderness

The area west of Fredericksburg known as the Wilderness of Spotsylvania—a second-growth forest scarred by abandoned mineral works—was as much a participant in the battle as the men who fought within it. The region’s dense undergrowth, felled trees, bramble-choked hollows, and narrow farm roads rendered cavalry nearly useless, negated field artillery, and throttled visibility to mere yards. General Hooker himself lamented:

“The rebels had found the key to the battlefield. The woods were their friend and our hindrance.”

Every regiment maneuvered blind. Brigade commanders, unable to see their flanks, were forced to guess at their positions. Firefights exploded with terrifying suddenness and vanished as quickly into the underbrush. This confusion contributed to several episodes of fratricide, none more tragic than the mortal wounding of General Stonewall Jackson.

Overview

The Battle of Chancellorsville, fought in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, is often regarded as Confederate General Robert E. Lee's greatest tactical success during the American Civil War. From May 1 to May 6, 1863, the battle saw important engagements that shifted momentum in favor of the Confederates, despite their numerical disadvantage against the Union Army of the Potomac, led by General Joseph Hooker.

Daily Events

- May 1, 1863: Hooker advanced towards Chancellorsville but halted and withdrew to defensive positions, ceding initiative to Lee. Skirmishes occurred along the Orange Turnpike and Plank Road, with the first shots fired at 11:20 a.m.

- May 2, 1863: Lee divided his army, and Jackson's 28,000 men executed a flanking march, attacking the Union XI Corps at 5:00 p.m., causing 2,500 Union casualties. Jackson was wounded by friendly fire that evening.

- May 3, 1863: Heavy fighting saw Lee launch multiple attacks, with Hooker injured by artillery, and Sedgwick's advance at Fredericksburg halted at Salem Church. Total casualties reached 21,357.

- May 4, 1863: Confederates pushed Sedgwick back across the Rappahannock, with 21,000 men facing him, while Hooker provided no assistance.

- May 5, 1863: Hooker ordered a retreat despite some commanders wanting to fight, with Union forces beginning to cross the Rappahannock.

- May 6, 1863: The Union retreat completed by 9:00 a.m., ending the campaign, with Confederate victory secured.

This battle highlighted Lee's strategic brilliance but also the high cost, including Jackson's death on May 10, impacting future Confederate efforts.

The Battle of Chancellorsville, May 1 to May 6, 1863

The Battle of Chancellorsville, fought from April 30 to May 6, 1863, in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, is a pivotal engagement of the American Civil War, often cited as Confederate General Robert E. Lee's greatest tactical victory. Despite being outnumbered nearly two to one by the Union Army of the Potomac, led by Major General Joseph Hooker, Lee's audacious strategies and Hooker's cautious decisions led to a significant Confederate triumph. However, this victory was tempered by the mortal wounding of Lieutenant General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, a loss that would have lasting consequences for the Confederacy. Below is a detailed day-by-day account of the battle from May 1 to May 6, 1863, drawing on multiple historical sources for accuracy and depth.

May 1, 1863: The Battle Commences

On May 1, 1863, the Union army, having crossed the Rappahannock River, was advancing towards Chancellorsville, aiming to outflank Lee's position at Fredericksburg. Hooker's forces, comprising approximately 70,000 men by this date, encountered Confederate resistance early in the day. The first shots were fired at 11:20 a.m., marking the beginning of hostilities. Along the Orange Turnpike, the Union Fifth Corps, under General George Meade, met General Lafayette McLaws's division, engaging in a three-hour battle before being pushed back. Similarly, the Union Twelfth Corps, led by General Henry Slocum, clashed with General Richard Anderson's division along the Orange Plank Road but was also stopped.

Surprisingly, Hooker, despite his numerical advantage, ordered a withdrawal to defensive positions at Chancellorsville by evening, ceding the initiative to Lee. This decision, later criticized as a tactical error, allowed Lee, with about 43,000 men at the Chancellorsville front, to plan his next move. The day's skirmishes set the stage for the intense fighting that would follow, with both sides testing each other's resolve.

May 2, 1863: Jackson's Flank Attack and Tragic Wounding

On May 2, Lee made one of his most audacious decisions: he divided his army again, sending Jackson with 28,000 men on a clandestine flanking march around the Union right flank. This move, executed through the dense Wilderness terrain, aimed to strike the Union XI Corps, commanded by General Oliver O. Howard, from an unexpected direction. At 5:00 p.m., Jackson's forces launched a surprise attack near Wilderness Tavern, shattering the XI Corps and pushing them back two miles. The attack resulted in 2,500 Union casualties, including 259 killed, 1,173 wounded, and 994 missing or captured, significantly weakening Hooker's right flank.

The day's success was marred by tragedy for the Confederates. After the attack, Jackson, while returning from a reconnaissance mission, was accidentally shot by his own troops at night. The friendly fire incident left him severely wounded, and General J.E.B. Stuart temporarily took command. Jackson's wounding would prove fatal, as he succumbed to complications on May 10, 1863, a loss Lee likened to losing his right arm.

May 3, 1863: The Climax of the Battle

May 3 saw the heaviest fighting of the campaign, with Lee launching multiple coordinated attacks against the Union positions around Chancellorsville. The battle was a slugfest in the wooded terrain, with Confederate artillery from Hazel Grove providing crucial support. By mid-morning, Southern infantry had united in the Chancellorsville clearing, pushing the Union forces back from Fairview by 10:00 a.m.

A critical moment occurred when Confederate artillery bombarded the Chancellor House, Hooker's headquarters. A cannonball struck a pillar, knocking Hooker unconscious for half an hour, further disrupting Union command and morale. The day's total casualties reached 21,357, equally divided between the two sides, reflecting the ferocity of the engagement.

Meanwhile, Union General John Sedgwick, commanding the VI Corps, had captured Fredericksburg and was advancing towards Chancellorsville to reinforce Hooker. However, Lee had anticipated this threat and sent forces under Generals Jubal Early and Lafayette McLaws to intercept Sedgwick. At Salem Church, Sedgwick's corps was engaged in a delaying action, halting his advance and preventing him from linking up with Hooker, thus isolating the Union efforts.

May 4, 1863: The Tide Turns Against Sedgwick

On May 4, the focus shifted to the area near Fredericksburg, where Lee ordered General Richard Anderson's division to join the battle against Sedgwick. Early's forces reoccupied Marye's Heights, and at 6:00 p.m., they launched an attack on Sedgwick's left-center, pushing him back. Despite being outnumbered—21,000 Confederate men facing Sedgwick's corps—the Confederates successfully halted the Union advance. Hooker, still recovering from his injury, provided no assistance, leaving Sedgwick to withdraw across the Rappahannock at Banks's Ford before dawn on May 5, effectively ending the Union threat from the east.

May 5, 1863: The Union Retreat Begins

By May 5, Hooker had decided to withdraw his forces, calling a council of war. Despite the majority of his corps commanders voting to continue fighting, Hooker ordered a retreat, initiating the Union army's crossing back over the Rappahannock River. Meade's V Corps served as the rear guard, with Confederate forces harassing the retreating troops but lacking the strength for a full pursuit. This decision marked the beginning of the end for the Union campaign at Chancellorsville.

May 6, 1863: The Retreat Completes

On May 6, the Union retreat was completed, with the last Federals reaching the north bank of the Rappahannock by 9:00 a.m. The pontoon bridges were pulled up, effectively ending the campaign. The Battle of Chancellorsville concluded with a decisive Confederate victory, with total casualties estimated at 30,764, including 17,304 Union (1,694 killed, 9,672 wounded, 5,938 missing & captured) and 13,460 Confederate (1,724 killed, 9,233 wounded, 2,503 missing & captured).

Analysis and Implications

The Battle of Chancellorsville showcased Lee's strategic brilliance, particularly his willingness to divide his army multiple times to outmaneuver and defeat a larger force. His decisions, such as Jackson's flank attack on May 2, were pivotal in securing the victory. However, the loss of Stonewall Jackson, who died from his wounds on May 10, was a devastating blow to the Confederate cause, weakening their leadership and strategic capabilities for future campaigns.

For the Union, the defeat was a bitter setback, leading to disenchantment with the war effort and further political turmoil. Hooker's cautious approach, particularly his decision to halt on May 1 and retreat on May 5, was widely criticized, contributing to his eventual resignation before the Battle of Gettysburg. The battle set the stage for future engagements, highlighting the challenges faced by the Union in defeating Lee's army.

Confederate Command and Rodes’s Division

When Hooker advanced his main force across the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers at the end of April, Lee executed one of the most audacious acts of operational division in military history. While leaving 10,000 men under Major General Jubal A. Early to hold the Fredericksburg heights, Lee and Stonewall Jackson marched westward to confront Hooker near the Chancellorsville crossroads.

By May 1, Hooker had entrenched in a defensive posture—an error Lee and Jackson would soon exploit. Jackson formulated a plan to attack the Union right flank, held by Major General Oliver O. Howard’s XI Corps. For this maneuver, Jackson divided his own Second Corps, placing the vanguard of the flanking column under Major General Robert E. Rodes, a bold and capable Alabama native.

Rodes’s Division – Order of Battle:

Commanding a newly independent division—his first such responsibility—Robert E. Rodes led approximately 8,000 men across the front of the unsuspecting Union army and launched the initial assault on May 2.

Brigadier General Alfred Iverson’s Brigade (North Carolina):

5th, 12th, 20th, and 23rd North Carolina Infantry

Brigadier General Junius Daniel’s Brigade (North Carolina):

32nd, 43rd, 45th, 53rd, and 2nd Battalion North Carolina Infantry

Brigadier General George Doles’s Brigade (Georgia):

4th, 12th, 21st, and 44th Georgia Infantry

Brigadier General Edward A. O’Neal’s Brigade (Alabama):

3rd, 5th, 6th, 26th, and 12th Alabama Infantry

Brigadier General Stephen D. Ramseur’s Brigade (North Carolina):

2nd, 4th, 14th, and 30th North Carolina Infantry

These brigades, especially Ramseur’s, spearheaded the assault with fanatical intensity. Ramseur’s North Carolinians tore into the startled Union camps in what Private George N. Bernard of the 12th Virginia Infantry called:

“A storm of yells and musket fire that turned men into beasts—howling, bayoneting, dragging wounded from their fires.”

Rodes’s formation broke through two Union lines in succession, the 11th Corps collapsing in disarray. Although temporarily checked near Dowdall’s Tavern by desperate Federal resistance, the attack marked one of the most decisive flank maneuvers of the entire war.

Union Forces and Command Breakdown

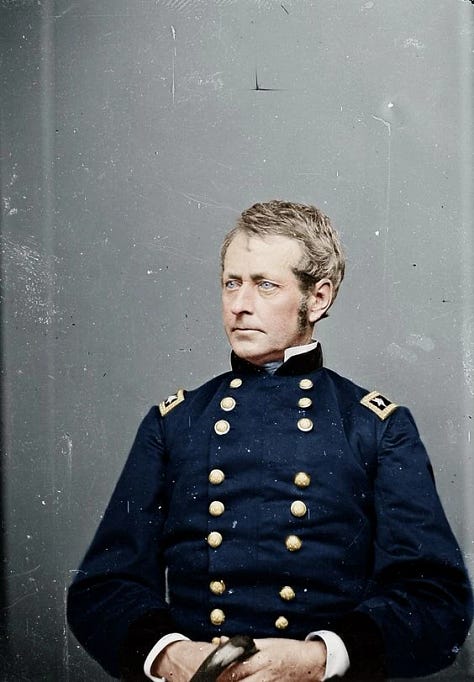

General Joseph Hooker, once confident to the point of arrogance—declaring “May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none”—became indecisive at the moment of truth. Despite commanding seven full corps (I, II, III, V, XI, and XII, plus the cavalry under Stoneman), Hooker surrendered initiative after the initial crossings.

A career U.S. Army officer and Mexican-American War veteran, Joseph Hooker secured a brigadier general’s rank in the Union Army in 1861. He first led a division of the Army of the Potomac near Washington, D.C., under Major General George McClellan. During the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, commanding the 2nd Division, III Corps, Hooker gained renown for bold leadership and dedication to his soldiers’ welfare. At Antietam, while leading the First Corps, a foot wound sidelined him. McClellan’s failure to chase Lee’s retreating forces led Lincoln to replace him with Major General Ambrose Burnside. After Burnside’s loss at Fredericksburg and further missteps, Lincoln appointed Hooker commander of the Army of the Potomac in early 1863.

As commander, Hooker improved troop conditions, enhancing food, medical care, and leave policies. At the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863, he devised an ambitious plan to outmaneuver Confederate General Robert E. Lee, splitting his forces to attack Lee’s army from multiple directions. Despite initial success, Lee’s daring counterattacks, led by Stonewall Jackson, caught Hooker off guard, leading to a devastating Union defeat. Conflicts with his officers and this loss prompted Hooker’s resignation from the Army of the Potomac command. In 1863, he moved to the Western Theater with the XI and XII Corps, joining the Army of the Cumberland. Victories at Lookout Mountain and the Battle of Chattanooga followed, and he excelled in the 1864 Atlanta Campaign under General William Tecumseh Sherman. From late 1864, Hooker led the Northern Department from Cincinnati, Ohio, until the war’s end.

Leaving active duty in 1866, he retired from the Army in 1868.

Major Federal Corps at Chancellorsville:

II Corps – Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch

Div. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, Gen. William H. French

XI Corps – Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard

Div. Gen. Charles Devens, Gen. Carl Schurz

XII Corps – Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum

Div. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams, Gen. John W. Geary

III Corps – Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles

Div. Gen. Hiram G. Berry, Gen. David B. Birney

V Corps – Maj. Gen. George G. Meade

I Corps – Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds

Cavalry Corps – Maj. Gen. George Stoneman

The failure of Howard’s XI Corps to adequately scout and prepare their flank permitted Jackson’s attack to achieve surprise. Survivors described being overrun in their sleep. One soldier from the 153rd Pennsylvania, a German-American unit, confessed:

“We had no time to fire... only to run.”

Jackson's Flank March and Fatal Wounding

On the night of May 2, shortly after the Confederate success, Jackson rode forward in the fading dusk to assess the potential for a night attack. A North Carolina picket line, mistaking his party for Federals, unleashed a volley that struck Jackson three times. His left arm was amputated. He died of pneumonia eight days later, on May 10.

General Lee, upon hearing of the loss, wrote:

“He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right.”

May 3–6: Bloody Continuation and Union Retreat

Despite the Confederate success on May 2, Lee now faced Hooker’s concentrated forces entrenched at Chancellorsville. On May 3, he launched frontal assaults led by McLaws, Anderson, and Early, recapturing the Chancellorsville house itself but suffering grievous losses.

That same day, General Sedgwick, operating east of Fredericksburg with VI Corps, finally stormed Marye’s Heights, only to be counterattacked and driven back by Early and reinforcements from Lee. Hooker, wounded by a falling artillery shell on May 3, relinquished command authority in spirit, if not formally. By May 6, he ordered a general withdrawal across the Rappahannock.

Casualties and Strategic Impact

Union: ~17,287 casualties (1,606 killed, 9,672 wounded, 5,919 missing/captured)

Confederate: ~13,303 casualties (1,665 killed, 9,081 wounded, 2,018 missing/captured)

The loss of Jackson outweighed the tactical victory. Lee emerged victorious, but without his most aggressive subordinate. Hooker was relieved of command within two months. Meanwhile, emboldened by success, Lee sought to carry the war north—toward Pennsylvania and its capital, Harrisburg.

Conclusion: Legacy of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville remains a paradox: a brilliant victory purchased at incalculable cost. It demonstrated the heights of Confederate generalship—Rodes’s Division a shining example of fresh leadership baptized by fire—yet also revealed the fragility of such a high-risk approach. The Wilderness cloaked mistakes, amplified fear, and rewarded audacity over caution. For the Union, it forced the realization that overwhelming numbers were meaningless without cohesion and reconnaissance. For the Confederacy, it created a vacuum of command that would be fatally exposed two months later, on the rolling hills of Pennsylvania.